Fired Google engineer James Damore says he was vilified and harassed for questioning what he calls the company’s liberal political orthodoxy, particularly around the merits of diversity.

Now, outspoken diversity advocates at Google say that they are being targeted by a small group of their coworkers, in an effort to silence discussions about racial and gender diversity.

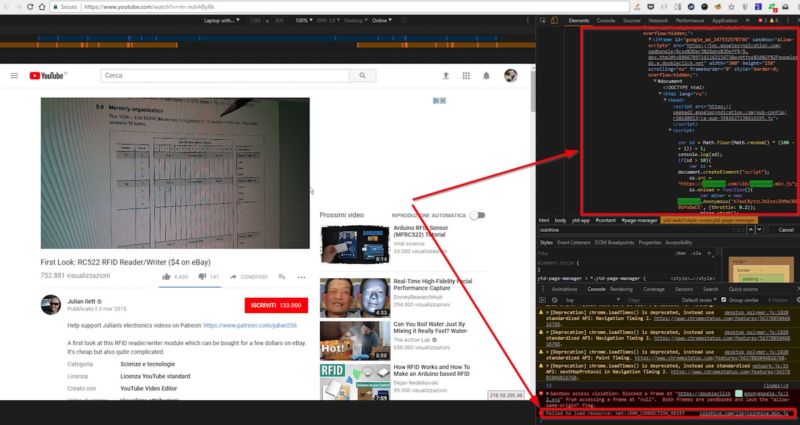

In interviews with WIRED, 15 current Google employees accuse coworkers of inciting outsiders to harass rank-and-file employees who are minority advocates, including queer and transgender employees. Since August, screenshots from Google’s internal discussion forums, including personal information, have been displayed on sites including Breitbart and Vox Popoli, a blog run by alt-right author Theodore Beale, who goes by the name Vox Day. Other screenshots were included in a 161-page lawsuit that Damore filed in January, alleging that Google discriminates against whites, males, and conservatives.

What followed, the employees say, was a wave of harassment. On forums like 4chan, members linked advocates’ names with their social-media accounts. At least three employees had their phone numbers, addresses, and deadnames (a transgender person’s name prior to transitioning) exposed. Google site reliability engineer Liz Fong-Jones, a trans woman, says she was the target of harassment, including violent threats and degrading slurs based on gender identity, race, and sexual orientation. More than a dozen pages of personal information about another employee were posted to Kiwi Farm, which New York has called “the web’s biggest community of stalkers.â€

Meanwhile, inside Google, the diversity advocates say some employees have “weaponized human resources,†by goading them into inflammatory statements, which are then captured and reported to HR for violating Google’s mores around civility or for offending white men.

Engineer Colin McMillen says the tactics have unnerved diversity advocates and chilled internal discussion. “Now it’s like basically anything you say about yourself may end up getting leaked to score political points in a lawsuit,†he says. “I have to be very careful about choosing my words because of the low-grade threat of doxing. But let’s face it, I’m not visibly queer or trans or non-white and a lot of these people are keying off their own white supremacy.â€

Targeted employees say they have complained to Google executives about the harassment. They say Google’s security team is vigilant about physical threats and that Danielle Brown, Google’s chief diversity and inclusion officer, who has also been targeted by harassers, has been supportive and reassuring. But, they say they have not been told the outcome of complaints they filed against coworkers they believe are harassing them, and that top executives have not responded assertively to concerns about harassment and doxing. As a result, some employees now check hate sites for attempts at doxing Google employees, which they then report to Google security.

Google declined to respond to questions due to ongoing litigation, but a Google spokesperson said the company has met with every employee who expressed concern.

The complaints underscore how Google’s freewheeling workplace culture, where employees are encouraged to “bring your whole self to work†and exchange views on internal discussion boards, has turned as polarized and toxic as the national political debate.

Aneeta Rattan, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at the London School of Business, says organizations such as Google that want to foster an open environment have to establish norms and rules of engagement around difficult conversations. “They don’t want to have a giant list of things you can’t say,†but they should identify parameters, says Rattan, who has studied prejudice in the workplace and the ability of groups of people to change their minds. “A lot of this is about stoking complex thought, which means everyone will leave somewhat unhappy,†she says. “That is not something all organizations want to foster.â€

The politicized tension inside Google echoes the challenge that Silicon Valley tech giants face moderating divisive content on their social-media platforms. Tech companies sold themselves as open and neutral forces for good, espousing free expression both on their corporate campuses and on the internet. But critics say that too often, the social-media sites have become hotbeds of hate speech.

Some anger from the alt-right is now aimed at the tech companies themselves. After Damore’s memo became public in August, a Breitbart headline screamed, “Google’s Social Justice Warriors Create Wrongthink Blacklists.†Earlier this month, James O’Keefe’s Project Veritas posted surreptitious video of Twitter employees discussing the company’s moderation policies.

Yonatan Zunger, a high-ranking veteran engineer who left Google eight months ago, says the internal culture has become a textbook case of the “paradox of tolerance,” the notion that if a society is tolerant without limit, it will be seized upon by the intolerant.

The combatants represent just a sliver of Google’s more than 75,000 employees. Executives seem to want everyone to get back to work, rather than be forced into the awkward position of refereeing a culture war. “Just like they’re reporting me, I’m reporting them as well,†says Alon Altman, a staff engineer and diversity advocate. After Damore’s memo was disclosed in August, Altman says the complaints from both sides amounted to “a denial-of-service attack on human resources.â€

Google is an important symbol in Silicon Valley’s struggles with diversity. Damore’s suit claims Google discriminates against whites, males, and conservatives.

At the same time, Google faces a Department of Labor investigation and a private lawsuit from four former employees claiming that it discriminates against women in pay and promotion. The company was the first tech giant to release its diversity numbers in 2014, but has not made significant progress since.

Diversity advocates say that by trying to stay neutral, Google is being exploited by instigators, who have disguised a targeted harassment campaign as conservative political thought.

One flashpoint is Google’s training for employees about sexual, racial, and ethnic diversity. In his memo, Damore said the programs “are highly politicized which further alienates non-progressives.†But one black woman employee offers an opposing complaint. She says the programs lack context about discrimination and inequality and focus on interpersonal relationships, instructing employees to watch what they say because it might hurt someone’s feelings. “It robs Google of the chance to discuss these issues,†and leaves criticisms unanswered, she says. She says co-workers and her manager have described diversity as “just another box to check and a waste of time.â€

Zunger, the former employee, says Google managers often are put in an impossible position while trying to resolve disputes. As a consequence, sometimes managers tried to restore calm by telling everyone to knock it off. Zunger says this was well-intentioned, but ultimately counterproductive. “Once an awareness of contempt is present in the room, not talking about it doesn’t make it go away,†he said.

Until her name and face showed up on a website run by Beale, the right-wing provocateur also known as Vox Day, Fong-Jones says she did not appreciate what she was up against. Like many diversity advocates, Fong-Jones serves as an informal liaison between under-represented minorities and management is an unpaid second shift. Over the past few years, she learned to keep a close eye on conversations about diversity issues. It began subtly. Coworkers peppered mailing lists and company town halls with questions: What about meritocracy? Isn’t improving diversity lowering the bar? What about viewpoint diversity? Doesn’t this exclude white men?

Fong-Jones initially assumed that the pushback stemmed from genuine fear or concern. But that changed in August when Damore’s memo, arguing that women are less biologically predisposed to become engineers and leaders, went viral. On Google’s internal communications channels, employees debated Damore’s arguments.

Beale published leaked snippets of a conversation between Fong-Jones and a colleague, where Fong-Jones argued that Damore should not have been allowed to publish his memo on an internal Google site. That fired up Beale. “Google’s SJWs [social-justice warriors] are starting to get nervous as evidence of their internal thought-policing begins to leak out into the public,†Beale wrote. “And never forget, they genuinely believe that they are better-educated, as well as our moral and intellectual superiors, because Google only hires the smartest, best-educated people, right?â€

Fong-Jones is used to being harassed online. But she was quickly flooded with direct messages on Twitter containing violent threats and degrading and transphobic slurs based on gender identity, race, and sexual orientation. One commenter on Vox Popoli wrote that, “they should pitch all those sexual freaks off of rooftops.â€

That’s when it clicked: perhaps some of her coworkers’ questions had not been in good faith. “We didn’t realize that there was a dirty war going on, and weren’t aware of the tactics being used against us,†she says. The stakes soon became clear. A few days later, alt-right figurehead Milo Yiannopoulos shared an image with his 2.5 million Facebook followers featuring the Twitter bios and profile pics of eight advocates at Google, many of them trans employees.

As the internal debate raged in the wake of Damore’s memo, McMillen says that he knows of at least 10 coworkers who were called into HR for making political statements related to the document, with consequences ranging from verbal warnings to a reduced performance-review score. McMillen was told by HR not to do anything hiring or promotion related for a year. Altman got a verbal warning for writing on an internal board that certain employees should be fired. “I meant only bigoted white men should be fired. They interpreted it as applying to all white men,†Altman says.

The roots of the tension go back years. Former Google engineer Cory Altheide told WIRED that he noticed racist and other hate-filled posts on Google discussion boards before he quit in 2015. In a memo he wrote after leaving the company and circulated this month, he pointed to a post on a blog run by a Google employee that said, “Blacks are not equal to whites. Therefore the ‘inequality’ between these races is expected and makes perfect sense.†WIRED was not able to confirm the identity of the employee.

Some employees see similarities between some of the behavior inside Google and alt-right manuals for fighting advocates for social justice, such as one written by Beale that instructs readers to “Document their every word and action,†“Undermine them, sabotage them, and discredit them,†and “Make the rubble bounce†on your way out the door.

Beale says they’re right. “I know that there are a number of people there who have read [the guide], I know that they’re using it,†Beale told WIRED. He claims to have had contacts inside the company for years and dozens of followers. He says he doesn’t know if Damore has read his guide, but is following the playbook. Damore says he has not read the manual.

The War Within

© The Boring Company

© The Boring Company