https://www.technologyreview.com/2020/08/26/1007611/how-qanon-is-targeting-evangelicals/

The first family to quit Pastor Clark Frailey’s church during the pandemic did it by text message. It felt to Frailey like a heartbreaking and incomplete way to end a years-long relationship. When a second young couple said they were doubting his leadership a week later, Frailey decided to risk seeing them in person, despite the threat of covid-19.

It was late May, and things were starting to reopen in Oklahoma, so Frailey and the couple met in a near-empty fast food restaurant to talk it over.

The congregants were worried about Frailey’s intentions. At Coffee Creek, his evangelical church outside Oklahoma City, he had preached on racial justice for the past three weeks. He says the couple didn’t appreciate his most recent sermon, which urged Christians to call out and challenge racism anywhere they saw it, including in their own church. Though Frailey tries to keep Coffee Creek from feeling too traditional—he wears jeans, and the church has a modern band and uses chairs instead of pews—he considers himself a theologically conservative Southern Baptist pastor. But at one point, the couple Frailey spoke to said they believed that he was becoming a “social justice warrior.”

Pastors and congregants disagree all the time, and Frailey doesn’t want to be the sort of Christian leader whom people feel afraid to challenge. But in that restaurant, it felt to him as if he and they had read two different sacred texts. It was as if the couple were “believing internet memes over someone they’d had a relationship with for over five years,” Frailey says.

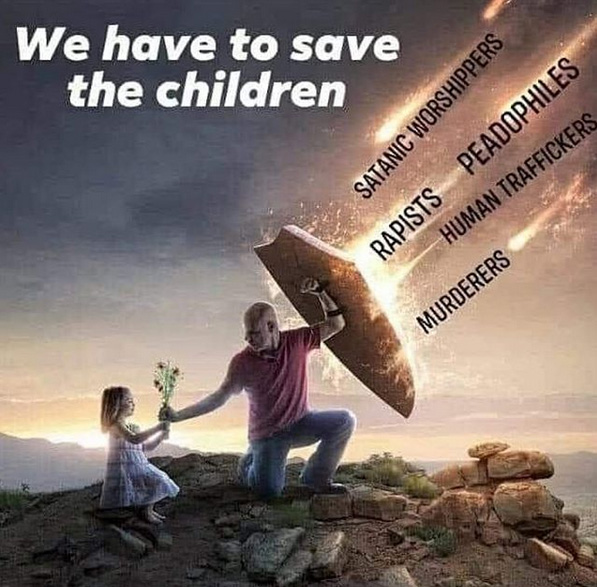

At one point he brought up QAnon, the conspiracy theory holding that Donald Trump is fighting a secret Satanic pedophile ring run by liberal elites. When he asked what they thought about it, the response was worryingly ambiguous. “It wasn’t like, ‘I fully believe this,’” he says. “It was like, ‘I find it interesting.’ These people are dear to me and I love them. It’s just—it felt like there was someone else in the conversation that I didn’t know who they were.”

Frailey told me about another young person who used to regularly attend his church. She was sharing conspiracy-laden misinformation on Facebook “like it’s the gospel truth,” he said, including a quote falsely attributed to Senator Kamala Harris. He saw another post from this woman promoting the wild claim that Tom Hanks and other Hollywood celebrities are eating babies.

Before the pandemic, Frailey knew a little bit about QAnon, but he hadn’t given such an easily debunked fringe theory much of his time. The posts he started seeing felt familiar, though: they reminded him of the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s and 1990s, when rumors of secret occult rituals tormenting children in day-care centers spread quickly among conservative religious believers who were already anxious about changes in family structures. “The pedophile stuff, the satanic stuff, the eating babies—that’s all from the 1980s,” he says.

That conspiracy-fueled frenzy was propelled in part by credulous mainstream news coverage, and by false accusations and even convictions of day-care owners. But evangelicals, in particular, embraced the claims, tuning in to a wave of televangelists who promised to help viewers spot secret satanic symbols and rituals in the secular world.

If the panic was back with fresh branding as QAnon, it had a new ally in Facebook. And Frailey wasn’t sure where to turn for help. He posted in a private Facebook group for Oklahoma Baptist pastors, asking if anyone else was seeing what he was. The answer, repeatedly, was yes.

The pastors traded links. Frailey read everything he could about QAnon. He listened to every episode of the New York Times podcast series Rabbit Hole, on ”what happens when our lives move online,” and devouring a story in the Atlantic that framed QAnon as a new religion infused with the language of Christianity. To Frailey, it felt more like a cult.

He began to look further back into the Facebook history of the young former member who had posted the fake Harris quote. In the past, he remembered, she had posted about her kids every day. In June and July, he saw, that had shifted. Instead of talking about her family, she was now promoting QAnon—and one member of the couple that had met with him in May was there in the comments, posting in solidarity.

Suddenly he understood that his efforts to protect his congregation from covid-19 had contributed to a different sort of infection. Like thousands of other church leaders across the United States, Frailey had shut down in-person services in March to help prevent the spread of the virus. Without these gatherings, some of his churchgoers had turned instead to Facebook, podcasts, and viral memes for guidance. And QAnon, a movement with its own equivalents of scripture, prophecies, and clergy, was there waiting for them.

“Don’t be deceived, my dear brothers and sisters.” —James 1:16

QAnon began in 2017 with a post on the /pol/ message board of 4chan—a particularly racist and abhorrent corner of a generally nasty online community where anyone can post anything anonymously. The poster, known only as “Q,” is QAnon’s prophet and source: the account is run by someone (or, most likely, a series of someones) who claims to have access to classified, inside information about Donald Trump’s true agenda, and a mission to spread that good news to the public.

Q’s posts contain clues, and adherents are told to decipher the messages and do independent research to uncover the secrets. The information they supposedly hold, promising a reckoning for all Donald Trump’s liberal enemies, has been proved untrue again and again, but the game continues. QAnon is extremely good at providing followers with an endless supply of hope. New posts appear regularly, and if reality doesn’t match the predictions about when, or how, the storm is coming for the world’s liberal elites, adherents simply shift their focus to something else.

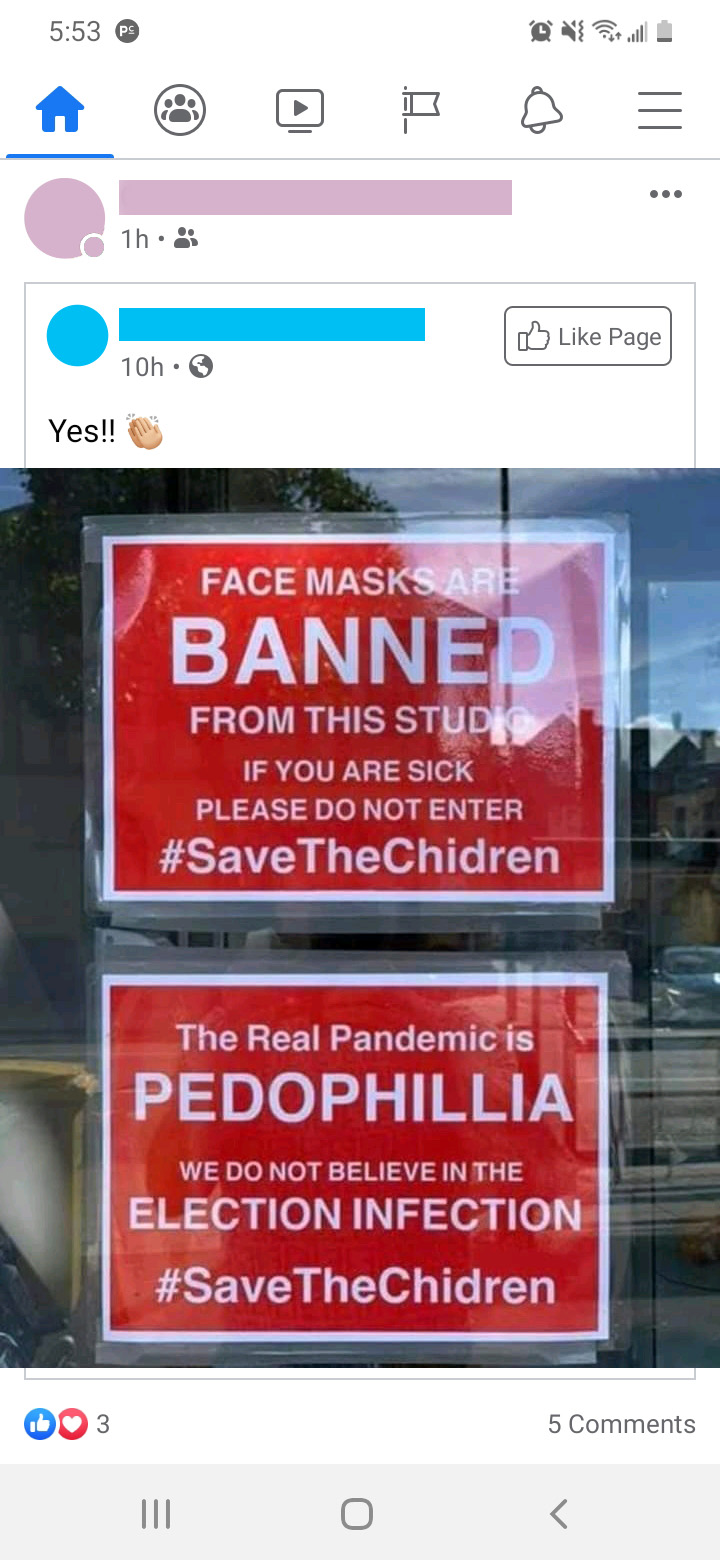

The tenets of QAnon are specific: that Trump is the chosen one to finally destroy a ring of Satanic pedophiles long protected by access to elite positions of authority, and that Q will provide the clues to lead followers to the truth. But the movement has mingled with so many other conspiracist causes and ideologies that it is now possible to be a carrier of QAnon content online without actually knowing what you are spreading. QAnon is now driving anti-mask activism and health misinformation campaigns, for example. There are QAnon politicians running for Congress. The beliefs have an affinity with apocalyptic Christianity, too, and there are resonances with Christian nationalism.

“QAnon is almost like a warehouse of different conspiracies that have been brought together and tied to a common warehouse owner,” says Ed Stetzer, a prominent evangelical author and the executive director of the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College.

Q has moved from site to site and now posts to a board called 8kun, whose predecessor 8chan was shut down after hosting multiple white supremacist manifestos and posts by mass shooters. QAnon is steeped in the extremism of its environment. The belief in “adrenochrome harvesting,” for example—that Hollywood elites are torturing children to derive a drug from their blood—is just another version of the ancient anti-Semitic blood libel.

This environment might not always seem hospitable to religion: on 4chan, for example, those who adhere to Christian traditions too earnestly are called “biblefags.” But Q invoked God early, says Brian Friedberg, a senior researcher at the Harvard Shorenstein Center’s Technology and Social Change project, who has studied QAnon since almost the very beginning.

“QAnon community construction, from the start, has emphasized a traditionalist American morality that is closely aligned with popular Christianity,” he says. “Q himself posts in a style that both invokes evangelical talking points and encourages deep scriptural research.”

QAnon followers will often repeat a commandment they learned from Q: that in the presence of doubt, you should “do your own research.” And that impulse will feel especially familiar to evangelicals, says William Partin, a research analyst at Data & Society’s Disinformation Action Lab, who has been studying QAnon. “The kind of literacy that’s implied here—close reading and discussion of texts that are accepted as authoritative—has quite a bit in common with how evangelicals learn to read and interpret the Bible,” he says.

Around a quarter of American adults identify themselves as evangelical Protestants, including parts of the Baptist, Lutheran, and Presbyterian denominations. This makes evangelicalism larger than any other religious stream in the US, including Catholicism and mainline Protestantism. But although QAnon has always carried religious overtones, its rising presence in evangelical circles is a relatively new development. In late February, the last time Pew Research polled American adults on QAnon, just 2% of white evangelical Protestants said they’d heard a lot about it, and another 16% said they knew just a little.

Kristen Howerton, a writer and family therapist who grew up evangelical, says that she began seeing more QAnon-related content from evangelical friends on Facebook about a year ago. Some were talking about Q, repeating and promoting the core tenets of the conspiracy theory. Many others, she guessed, didn’t know the totality of the QAnon beliefs, or even that the reason they were being exposed to the conspiracy theory was its vast social-media network. But they knew they agreed with what they were hearing—that liberals were evil, and that Trump was going to stop them—and they found that good enough reason to share QAnon’s ideas on their own social feeds, helping them spread.

“These are not the people who were spending time on 4chan or 8chan four years ago,” Howerton says. “They’re getting their info from other Facebook posts. it’s not a primary-source crowd.”

This is why social media makes such a great mission field for QAnon. Facebook and Twitter give its evangelists the easiest and best chance of reaching new people with their message (or more mainstream-friendly versions of it)—powered by the platforms’ recommendation algorithms, which are designed to show people things they’re likely to have an affinity for.

The platforms have started trying to dampen the influence of QAnon, particularly after it began to intersect with pandemic conspiracy theories. Facebook shut down hundreds of QAnon pages and accounts last week after an internal study revealed that QAnon-associated groups had millions of members, while Twitter has banned thousands of accounts for “coordinated harmful activity.”

Some say it’s too late. QAnon has manipulated Twitter hashtags and been amplified by the president, who has retweeted QAnon-affiliated Twitter accounts more than 200 times. It also has its own celebrities, a kind of priest class of influencers with YouTube channels and Patreons who promise to show their fans the way. Among them is David Hayes, “the Praying Medic,” whom the Atlantic called “one of the best-known QAnon evangelists on the planet.” In one recent video, he told his 379,000 YouTube subscribers, “The movement that Q has started is drawing a lot of people to consider God.”

Another popular QAnon influencer, Blessed2Teach, whose followers are known as “Christian Patriots,” recently told them in a YouTube livestream that “the cabal spends more money trying to infiltrate pastors than anything,” and that “many many of the megachurches have taken cabal funding.” As The Conversation noted in May, there are pastors who have begun bringing QAnon into their Zoom sermons. And Frailey, the Oklahoma pastor, found that even though many colleagues in the Facebook group where he had posted were worried about the spread of QAnon in their churches, others defended it.

Joe Carter, the executive pastor of McLean Bible Church Arlington in Virginia and an editor of the conservative Christian publication The Gospel Coalition, published an FAQ on QAnon in May. He decided to dig into the topic after hearing from dozens of pastors asking for advice on how to stop its growing influence in their communities, he told me.

“Although this movement is still fringe, it is likely that someone in your church or social-media circles has either already bought into the conspiracy or thinks it’s plausible and worth exploring,” Carter wrote.

“I can see people I care about, respect, are great, are just super-susceptible to this thing,” said a youth pastor who declined to be named in this piece for fear of retaliation from QAnon believers but has been raising the alarm at his conservative-leaning Lutheran church. “If we can get ahead of this, we might be able to do some damage control before it metastasizes.”

Their task has been made more difficult as QAnon has started linking up with other conspiracy theories, particularly around the covid-19 pandemic: misinformation about masks, anti-vaccination theories, and claims that lockdowns are a liberal plot to control the population, for instance. And more recently, its believers have found even better vectors.

“The name of the LORD is a fortified tower; the righteous run to it and are safe.” —Proverbs 18:10

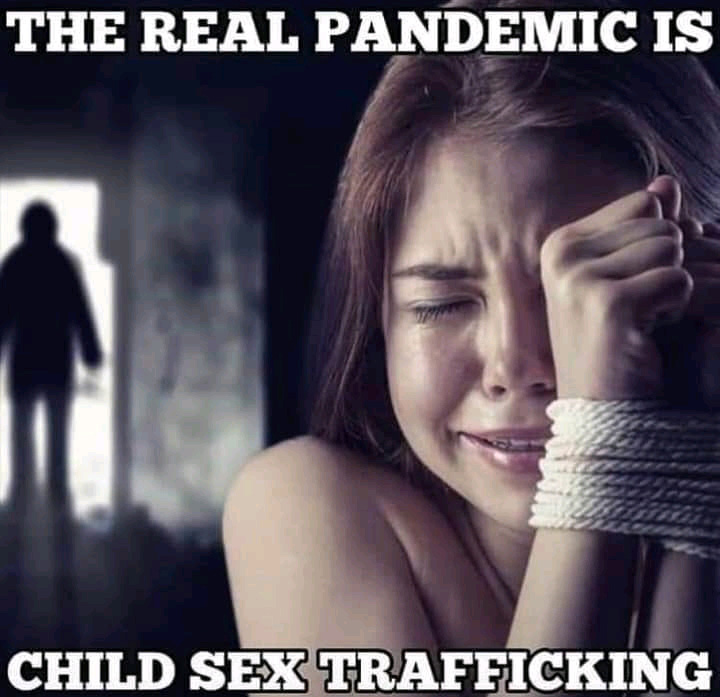

One Friday in mid-July, Twitter saw a strange new hashtag rise up out of nowhere: #Wayfair, the name of an online furniture company. It was trending because of a baseless conspiracy theory that listings for suspiciously high-priced cabinets were named after missing children. Perhaps, the theory went, this was a method human traffickers and child abusers used to secretly signal and sell victims to one another. This was debunked numerous times, but the meme quickly spread to Instagram, TikTok, and Facebook. On each site, people moved by the very human impulse to care about vulnerable children began repeating what they saw to their friends and followers.

For evangelicals, the Wayfair rumors exploded into a major online freakout. Howerton, the family therapist, was alarmed when she saw her friends posting about it, including members of the megachurch she used to attend. She’d used her platform for years to raise awareness about child trafficking, but with just a little rudimentary research, she quickly learned that the claims weren’t true. And then she spotted where they had originated. “I went down a lot of rabbit holes,” she says. “Then I got the QAnon connection.”

“It was Wayfair that really opened my eyes to which of my friends were really following the QAnon stuff. And it was a lot,” she says.

The Wayfair conspiracy theory was a prelude to a much bigger social-media push: #SaveTheChildren. In July, as Mel Magazine has documented, this and other existing hashtags were flooded on Facebook and Instagram with QAnon memes about pedophile rings and the Clintons. That then inspired a series of rallies across the country. Some of them, NBC News reported, were organized by figures who implicitly or explicitly support QAnon, and some marchers brought signs with QAnon slogans. Some legitimate human-rights organizations have told the New York Times that they hope the wave of conspiracy-fueled interest could translate into genuine support for those who are trying to actually save children, but others have been overwhelmed with false reports and nonsense tips.

Child abuse and human trafficking are, of course, real and terrible phenomena, and they are familiar topics in many evangelical churches. “Saving” children, whether by adoption, anti-trafficking activism, or opposition to abortion, drives a great deal of evangelical activism. It’s not uncommon for a church to partner for fundraising or support with a religious or secular nonprofit that helps trafficking victims.

Carter, of the Gospel Coalition, says this well-meaning drive to help is also easily exploited. Among evangelicals, feelings about human trafficking are often so intense that people are only interested in hearing, and sharing, stories about how inhumane and widespread it is. In Carter’s experience, his audience is particularly hostile to being told that a trafficking story being shared isn’t true. “If it’s a problem, it has to be a huge problem. If you try to put it into context, it’s seen as downplaying the problem,” he says.

Howerton believes it’s no accident that QAnon has taken hold among evangelicals now: they are facing tremendous cognitive dissonance. “I was raised evangelical Christian Republican. There is nothing that makes sense for Trump with any of the values that I was raised with,” she says. “There’s a part of me that thinks that this is a very elaborate false narrative to explain their continued loyalty to Trump.”

Wheaton College’s Ed Stetzer says that QAnon resonates with Christian religious thought by presenting itself as a force for good, designed to destroy evil. But Jason Thacker, chair of research in technology ethics at the Southern Baptist Convention’s Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, says Christian followers of QAnon are wrong about what side it’s on. “QAnon is not about sex trafficking,” he says, but “taking advantage of gospel conventions and manipulating them for purposes of power.”

“It’s wrong. It’s evil,” he says. “The reason—Christians of all people should be the first to stand up and fight against these things—is that it’s not true.”

“Keep your tongue from evil and your lips from speaking deceit.” —Psalm 34:13

Over the years, QAnon has demonstrated some of the dangers of letting misinformation flourish online. The FBI has concluded that this and other extreme conspiracy theories carry a potential for inspiring violence. Some followers have already committed destructive, sometimes violent, acts in the name of their beliefs.

But Stetzer, of the Billy Graham Center, worries that evangelical Christians face a unique threat from QAnon. It might compromise their ability to do one of the most important things they can do: bear witness to what they believe, and share those beliefs with others.

“As an evangelical Christian, I’ve already got some things that I believe that the mainstream would consider conspiracy,” he says. When Christians believe and propagate foolish things like QAnon, they make it even harder for others to listen.

Right now, the evangelical leaders who are concerned about QAnon and misinformation in their communities are running to catch up. Many of them are too busy helping their congregations deal with the direct impact of the pandemic to spend much time countering conspiracy theories. Howerton thinks they’re just beginning the process of figuring out what to do about QAnon. She was planning on writing a newsletter to help her readers understand what’s going on with their relatives who have fallen into this. But a bigger, organized effort still hasn’t formed.

“I feel like a failure,” Frailey, the Oklahoma pastor, says. “We weren’t able to provide a good enough community in this time of separation. We weren’t able to provide what was needed. The technology wasn’t good enough.” Carter echoes him: “I’ve talked to a lot of pastors who assume I know what to do. And I definitely don’t.”

The Bible provides some guidance on how to act online, Thacker notes: the Epistle of James, for instance, is about how to persevere through a crisis or trial. James 1:19 reads: “Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires. Therefore, get rid of all moral filth and the evil that is so prevalent and humbly accept the word planted in you, which can save you.”

“We should be the people who are slowing down online, in a culture that is going faster and faster,” Thacker says. Instead, the opposite seems to be happening.

For Frailey, the best thing he can do is keep his door open for all, including those who have left. Just because someone has descended into QAnon doesn’t mean they can’t come back from it. When we spoke, Frailey was torn between sharing his story, which he feels could help other pastors and Christians realize they aren’t alone, and making sure he isn’t shutting the door forever on the families who have walked away from his church.

“I’m just trying to keep a line out here to say, ‘Hey, if you fall into this, you can come back,’” he says. So far, though, “there haven’t been any saves.”

—Some of the images in this story have been anonymized to protect the individuals who posted and interacted with them.

via Technology Review Feed – Tech Review Top Stories https://ift.tt/1XdUwhl

August 26, 2020 at 04:25AM