For over 100 years, quantum physics has taught us that light is both a wave and a particle. Now, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have performed a daring experiment using single atoms that confirms that, while light can behave as either a particle or a photon, it cannot be seen to behave as both at the same time.

The debate about the nature of light goes back centuries, to the 17th century and the time of Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens. Some, like Newton, believed that light had to be made from particles to explain why mirror images are sharp and our inability to see around corners. And yet, Huygens and others pointed out, light exhibits wave-like behavior, such as diffraction and refraction.

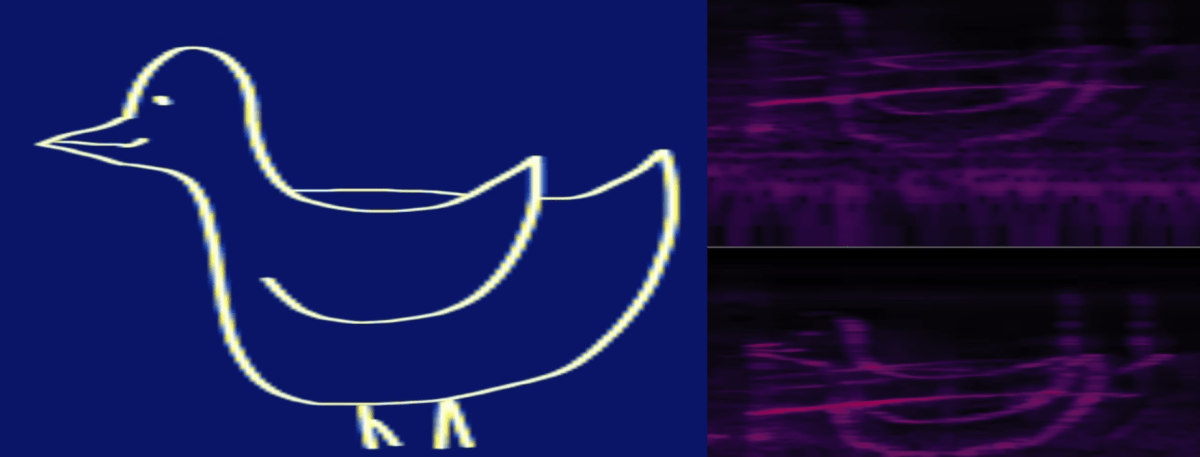

In 1801, the physicist Thomas Young devised the famous double-slit experiment, where he shone a coherent light source through two narrow slits and onto a wall. If light were a particle, we would expect two overlapping spots of light to appear on the wall as different photons pass through each of the two slits. Instead, what Young found was that the light was spread out on the wall in alternating interference patterns of light and dark. This could only be explained if light waves were spreading out from each slit and interacting with one another, resulting in constructive and destructive interference.

A century later, Max Planck showed that heat and light are emitted in tiny packets called quanta, and Albert Einstein showed that a quantum of light is a particle called a photon. What’s more, quantum physics showed that photons also display wave-like behavior. So Newton and Huygens had both been correct: light is both a wave and a particle. We call this bizarre phenomenon wave-particle duality.

Yet the uncertainty principle states that we can never observe a photon acting as both a wave and a particle at the same time. The father of quantum physics, Niels Bohr, called this "complementarity," in the sense that complementary properties of a quantum system, such as behaving like a wave and a particle, can never be simultaneously measured.

Einstein was never a lover of the randomness that complementarity and the uncertainty principle introduced into the laws of nature. So he looked for ways to disprove complementarity, and in doing so he went back to Young’s classic double-slit experiment. He argued that, as a photon passes through one of the slits, the sides of the slit should feel a small force as they are "rustled" by the passing photon. In this way, we could simultaneously measure the light acting as a photon particle as it moves through a slit, and as a wave when interacting with other photons.

Bohr disagreed. The uncertainty principle describes how, for example, we cannot know a photon’s momentum and its exact position — both complementary properties — at the same time. Therefore, said Bohr, measuring the "rustling" of the passing photon would only result in scrubbing out the wave-like behavior, and the interference pattern produced by the double-slit experiment would be replaced with just two bright spots.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Experiments over the years have shown Bohr to be correct, but there’s always been the small, nagging doubt that bulky apparatus could introduce effects that mask seeing light as a wave and a particle simultaneously.

To address this, the MIT team, led by physicists Wolfgang Ketterle and Vitaly Fedoseev, pared the double-slit experiment down to the most basic apparatus possible, at the atomic scale. Using lasers, they arranged 10,000 individual atoms cooled to just fractions of a degree above absolute zero. Each atom acted like a slit, in the sense that photons could scatter off them in different directions and over many trials produce a pattern of light and dark areas, based on the likelihood that a photon will be scattered in certain directions more than others. In this way, the scattering produces the same diffraction pattern as the double-slit experiment.

"What we have done can be regarded as a new variant to the double-slit experiment," said Ketterle in a statement. "These single atoms are like the smallest slits you could possibly build."

The experiment showed that Bohr was definitely correct when he argued for complementarity, and that Einstein had got it wrong. The more atom-rustling that was measured, the weaker the diffraction pattern became, as those photons that were measured as particles no longer interfered with the photons that hadn’t been measured to be particles.

The experiments also showed that the apparatus — in this case the laser beams holding the atoms in place — did not affect the results. Ketterle and Fedoseev’s team were able to switch off the lasers and make a measurement within a millionth of a second of doing so, before the atoms had a chance to jiggle about or move under gravity. The result was always the same — light’s particle and wave nature could not be simultaneously discerned.

"What matters is only the fuzziness of the atoms," said Fedoseev. This fuzziness refers to the quantum fuzziness that surrounds an atom’s exact position, as per the uncertainty principle. This fuzziness can be tuned by how firmly the lasers hold the atoms in position, and, the more fuzzy and loosely held the atoms are, the more they feel the photons rustling them, therefore revealing light as a particle.

"Einstein and Bohr would have never thought that this is possible, to perform such an experiment with single atoms and single photons," said Ketterle.

The experiment further cements the weirdness of quantum physics, in which particles have a dual nature, and we can never simultaneously measure complementary properties such as whether light is a wave or a particle, or the position and momentum of that particle. The universe seems to operate on the basis of probability, and the emergent properties that we see coming from the quantum realm are only the manifestation of statistics involving very many particles, all of which, to Einstein’s chagrin, "play dice."

The research was published on July 22 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

via Latest from Space.com https://www.space.com

July 31, 2025 at 04:01PM