There’s a type of knife tech often seen in science fiction that revolves around vibrating a blade to increase its sharpness. We’ve seen examples of this in franchises like Star Wars (vibroblades), Evangelion (the prog knife), Dune (pulse-swords) and the Marvel universe (vibranium), but what might surprise you is that the underlying science is sound. By vibrating a cutting tool at high frequencies, not only do you reduce friction, you essentially turn the blade into a saw, as tiny oscillations enhance the inherent sharpness of a blade.

However, up until recently, this tech largely only existed in fiction or for large companies that have the money to utilize the tech on an industrial scale. But that’s changing in a big way for home cooks this year thanks to Seattle Ultrasonics, which is releasing the world’s first ultrasonic chef’s knife: the C-200. After chopping, smashing and cooking with it for about a month, I’m convinced that this is the future of kitchen knives.

Design

From afar, the C-200 looks a lot like a regular 8-inch chef’s knife, but with a slightly more contemporary design. It features a three-layer san mai blade made from Japanese AUS-10 steel with a 13-degree edge angle per side (26 degrees total). However, upon closer inspection, you’ll notice there are some features that seem a bit out of place on a premium knife.

The first is that the C-200 doesn’t have a full tang, which is the back end of a blade that ideally extends into the handle to provide added strength and durability. This is usually a major no-no, particularly on a $400 knife. However, when you consider that Seattle Ultrasonics needed somewhere to put its vibration tech, there really isn’t any room for it other than inside the knife’s grip.

The knife’s second quirk is that the back of the plastic handle features small indicator lights on either side, which is obviously a bit weird. Furthermore, the entire gray section can be removed to reveal a small 1,100mAh battery with an onboard USB-C port. Frankly, the presence of a battery in a knife is just kind of funky. But hey, the power to vibrate the knife has to come from somewhere because it definitely isn’t being generated by your hands. And while Seattle Ultrasonics doesn’t include a charging adapter or cable in the box, I don’t mind because the company wisely took cues from the larger gadget industry and went with a power spec that’s already widely in use. Honestly, I wish more kitchen tech makers would do the same.

However, the knife’s biggest oddity is the big orange button on the bottom of its handle. This is what you use to make the blade vibrate, which it does at 33kHz. It’s positioned well so that it’s easy to press regardless of whether you do a traditional pinch grip or if you’re a bit more casual and prefer to hold the knife only using its handle. In the future, I can see this button becoming a touch-sensitive sensor, but for now, it’s simple and effective.

The main downside to the C-200’s design is that at 328 grams (around 0.75 pounds) it’s heavier and bulkier than a typical knife. When compared to other knives I own, which are made from a wide variety of materials including, ceramic, molybdenum steel, carbon steel and even titanium carbide, it weighs more than everything else aside from my big Chinese cleaver (396 grams). And while it fits nicely in my hand, my wife said it takes a bit more effort for her to wield. It’s not too much to the point where you don’t want to use it. But for quick tasks, sometimes I found myself subconsciously reaching for lighter options like my 6-inch ceramic knife, which weighs just 97 grams.

How it works

From a user standpoint, putting the C-200 to work couldn’t be simpler. Just press the button and let the knife do its thing. The big difference from how knives like this work in sci-fi is that there’s no audible hum or detectable vibration when it’s on. It’s practically silent (well, most of the time, but more on that later), so you have to trust that it’s on or check the indicator light on the handle. That said, if you still don’t believe anything is happening, you can run the edge of the blade under water or scrape it over some cut citrus, at which point the blade’s vibration will atomize nearby liquid into a fine mist. It’s a cool party trick that also doubles as a way to amp up a cocktail by adding a faint essence of lemon, lime or anything else you can think of.

Inside, the knife relies on PZT-8 piezoelectric ceramic crystals to generate up to 30,000 vibrations per second, which propagate down the blade and make the knife function as if it’s sharper than it actually is. This all sounds rather fantastic, so how does it function in the real world?

In-use

To really put the C-200 through its paces, I cooked over a dozen meals that involved neatly slicing or preparing a wide variety of foods — including Hasselback potatoes, flank steak, pork belly, chives, sushi-grade tuna and all sorts of fruit.

In short, the C-200’s effectiveness depends a lot on what you’re chopping. For soft things like strawberries or a piece of cake, I didn’t notice much of a difference. To make things even more difficult, the knife arrived out of the box with an incredibly fine edge — the kind that makes shearing through a sheet of paper child’s play. So even though Seattle Ultrasonics says its knife can reduce cutting effort by up to 50 percent, there’s not much gain to be had when slicing foods that could just as easily be cut by a butter knife.

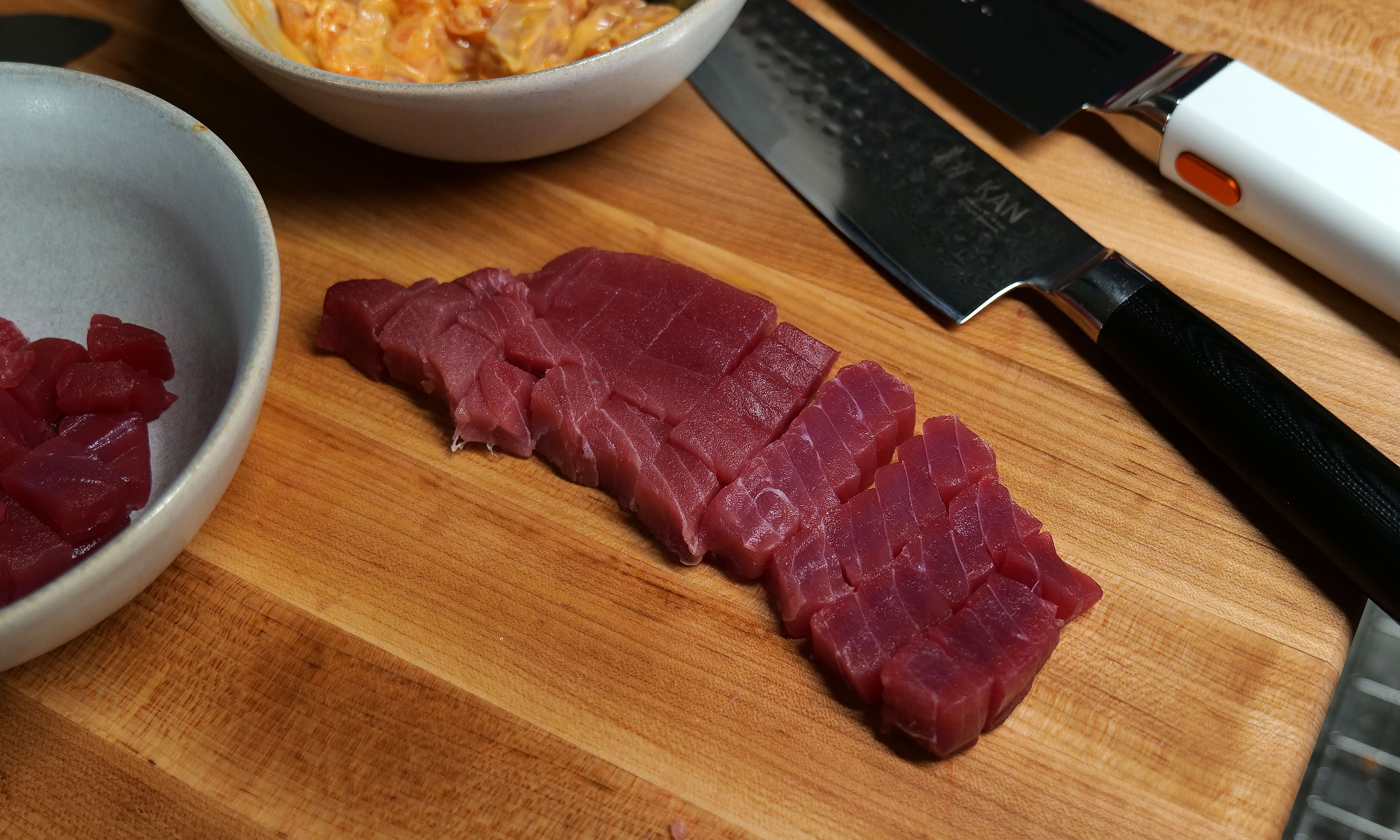

However, as I used it more, I found that the C-200 excels at cutting through delicate items like tomatoes, scallions and fish, where using a dull knife often results in bruising the food as you chop. This was most evident when I made poke at home, where Seattle Ultrasonic’s knife delivered cleaner, more precise cuts than anything else I own.

When I whipped up some pico de gallo, I distinctly noticed how neatly the C-200 sliced through the skin of a tomato, instead of initially putting a crease in it before cleanly passing through its interior — which often happens when using dull knives. An additional benefit is that because of the vibrations, I found some foods like garlic didn’t stick to the side of the blade as much. This made it easier to keep track of how much I chopped while simultaneously reducing the mess from things falling willy-nilly during prep. But perhaps the most obvious demonstration of the knife’s prowess was when I diced an onion. When using my other knives or the C-200 without powering it on, I could feel when I tried to cut through thicker, more sturdy layers. But then, at the touch of a button, I was able to slice down with practically no resistance. It’s almost shocking because it feels like magic.

The C-200 even has the ability to reduce the importance of certain knife techniques. Anyone who’s seen all the posts on r/kitchenconfidential about cutting chives will already know what I’m talking about. As J Kenji Lopez-Alt neatly demonstrated, the ideal way to get crisp, clean slices is to do a subtle forward or back cut instead of simply chopping straight down. But with Seattle Ultrasonics’ knife, I’ve found that it’s so sharp you can get away with almost any motion and still get good results. And if you do it the right way, things are even better.

Other types of food that makes the C-200 really shine are denser ingredients like meat and potatoes, where you can really feel the added cutting power. Previously, when I had to break down thick cuts of protein, I sometimes wished I owned a serrated electric knife. You know, the kind you break out once a year on Thanksgiving and then it sits and gathers dust for the other 364 days. But the C-200 made that desire a thing of that past, as it quickly and easily worked through flank steak while once again producing neat, uniform slices.

My favorite application of the C-200 was when I was doing prep for Taiwanese braised pork (aka ???). Despite this being one of my most beloved dishes that I taught myself how to cook because I couldn’t easily find it from local restaurants, I don’t make it very often because it’s a lot of work to cut multiple pounds of pork belly into small lardon-shaped pieces. Here, the knife’s vibrations made it so much easier to cut through all those layers of meat, fat and skin. If there’s any situation where the C-200 makes it 50 percent easier to slice through something, it’s this.

During my testing, two small issues cropped up. While it was quite rare, the knife would sometimes emit a faint high-pitched whine. When I asked Seattle Ultrasonic’s founder Scott Heimendinger about this behavior, he was rather frank, saying that this can occur when water or moisture accumulates in just the right spots on the blade. Furthermore, he said this only happens on a small number of V1 models, which the company is working to fix in the future. Thankfully, I don’t mind, but if it bothers you, making the noise go away is as easy as wiping down the knife down with a cloth or paper towel.

The other complication came while I was working through the multiple pounds of pork belly I mentioned earlier. After 10 to 15 minutes of continuous use, the knife beeped and its indicator light turned red. Turns out the knife had overheated, which was something I had not even considered. This led to higher-than-normal temperatures inside the knife’s sealed electronics causing it to shut off. But after just 30 seconds, it returned to form. During later uses, I learned that simply taking my finger off the button between tasks, which happens naturally as you prep anyway, was more than enough to stop that situation from happening ever again.

On the flipside, I was happy to discover that despite lacking a full tang, the C-200 can handle fairly rough tasks, including laying the knife on its side to smash garlic or jamming it into an avocado to remove its pit. That said, I would really recommend against doing the latter, because between its inherent sharpness and its vibration tech, this is the first knife I’ve used that can slice cleanly through an entire avocado with almost no extra effort.

Cleaning and care

The last big concern about a knife with built-in electronics is how it handles clean-up. Thankfully, the C-200 features an IP65 rating for dust and water resistance. That means it can withstand rinsing and splashes without issue. And it’s actually even tougher than that, because the front of the knife, including its bolster and button, are rated IP67. This means it can take full submersions in water if need be. However, just because you can, doesn’t mean you should. Good kitchen protocol says you don’t throw knives you care about in the sink and forget them, just like how you wouldn’t put one in the dishwasher either.

But perhaps the greatest advantage of this tech is that it allows you to go longer between needing to get your knives sharpened, which if you’re like most home cooks, is probably never. To be clear, I haven’t tested this and in some respects I wish I had been able to test out a dull version of the C-200. That said, science dictates that slice for slice, an ultrasonic knife will simply cut better than an equivalent blade without the extra tech. So if you believe in the adage that a dull knife is more dangerous than a sharp one because you need to apply more force to get the same results, this is another bonus for both safety and convenience.

The not-so-optional accessory

I fully admit the need to keep a knife charged up is a major annoyance and something I or anyone else probably doesn’t want to do. Thankfully, Seattle Ultrasonics thought of that by including support for wireless charging via the C-200’s magnetic tile and it’s dead simple to use. Just toss it on the charger when you’re not using and it will take care of itself, so you never have to worry about how much of its normal 20-minute runtime it may or may not have left. There are also holes around back so you can easily mount the charger on a wall or shelf. In short, the added convenience the charging tile brings is so valuable that I don’t really consider it an optional accessory. If you’re getting the C-200, you need to buy this too, which sadly means you’re looking at an all-in price of $500 for the bundle instead of just $400 for the knife by itself.

Wrap-up

After using the C-200, I don’t think people need to rush out and throw all their old-school knives in the trash. The beauty of an ultrasonic blade like this is that it can handle everything your old cutlery is meant for, but with the touch of a button, it delivers sharpness unlike anything you’ve experienced before. And while it has some quirks, they’re nothing like the kind you typically encounter on first-gen gadgets. Its biggest drawback is that its magnetic charging tile feels like an essential accessory, but it adds extra cost on top of a product that already has a deservedly premium price tag.

Even though I’m sure knife makers will continue tweaking blade shapes and alloy mixes from now until the end of time, the addition of ultrasonic vibrations to a chef’s knife unlocks a completely new tier of performance. That’s because this technology is additive. All it does is enhance what a blade already does best. And when you look at related gadgets in the maker space, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that there’s a similar revolution that resulted in Adam Savage of Mythbusters fame naming a sonic cutter as one of his favorite things of 2025. When viewed that way, it makes me even more confident that the C-200 is the flagbearer for a new breed of kitchen knives.

This article originally appeared on Engadget at https://ift.tt/Mow1xnc

via Engadget http://www.engadget.com

February 24, 2026 at 08:08AM

(@gonzague)

(@gonzague)