Magnet Collisions in Super Slow Motion [Video]

https://ift.tt/2IzeSVa

![Magnet Collisions in Super Slow Motion [Video]](https://i2.wp.com/www.geeksaresexy.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/magnet.jpg?fit=1200%2C604&ssl=1)

Magnet Collisions in Super Slow Motion [Video]

Advertisement

Tech

via [Geeks Are Sexy] Technology News https://ift.tt/23BIq6h

May 20, 2018 at 04:17AM

For everything from family to computers…

Magnet Collisions in Super Slow Motion [Video]

https://ift.tt/2IzeSVa

![Magnet Collisions in Super Slow Motion [Video]](https://i2.wp.com/www.geeksaresexy.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/magnet.jpg?fit=1200%2C604&ssl=1)

Advertisement

Tech

via [Geeks Are Sexy] Technology News https://ift.tt/23BIq6h

May 20, 2018 at 04:17AM

Google, Alibaba Spar Over Timeline for ‘Quantum Supremacy’

https://ift.tt/2IQBmk2

Google’s quantum computing researchers have been planning a party—but new results from a competing team at China’s Alibaba may have postponed it. The China-America corporate rivalry on an obscure frontier of physics illustrates a growing contest between nations and companies hoping to create a new form of improbably powerful computer.

In March, Google unveiled a chip called Bristlecone intended to set a computing milestone. It could, Google said, become the first quantum computing system to perform a calculation beyond the power of any conventional computer—a marker known as quantum supremacy. The group’s leader, John Martinis, suggested it could reach supremacy this year, updating an earlier prediction that his team might do so in 2017.

But new results from Alibaba’s quantum researchers suggest Google’s published plans for Bristlecone can’t achieve quantum supremacy after all. Chips with lower error rates will be needed, they argue. In an email, Google researcher Sergio Boixo told WIRED that he welcomes such research, but there are “a number of questions” about the paper’s results. Others see them as notable. “The goalposts have moved,” says Itay Hen, a professor at the University of Southern California.

Achieving quantum supremacy would be a scientific breakthrough, not a sign that quantum computers are ready to do useful work. But it would help Google’s standing in an intensifying competition to make practical quantum computers a reality. The search company and competitors like IBM, Intel, and Microsoft want to rent or sell quantum computers to companies such as Daimler and JP Morgan, which are already exploring how the machines might improve batteries and financial models.

Computers like the one forming these words use pulses of electricity to represent data as bits, 0’s or 1’s. Quantum computers encode data into quantum mechanical effects of the kind that perplexed Albert Einstein and other physicists in the early 20th century, to create qubits. The exotic devices operate at temperatures close to absolute zero. In groups, qubits can zip through some tough calculations using tricks such as attaining a “superposition,” something like both 1 and 0 at the same time. There’s evidence that could aid chemistry simulations; Google and others think machine learning could get a boost, too.

Google’s Bristlecone chip has 72 qubits made with superconducting circuits, the largest such device ever made, ahead of IBM’s 50-qubit device and one from Intel with 49. Google’s researchers calculated that was enough to run a carefully chosen demonstration problem beyond the reach of any conventional computer, achieving quantum supremacy.

‘This suggests that we won’t be seeing a demonstration of quantum supremacy anytime soon.’

Graeme Smith, University of Colorado

Researchers at Alibaba, China’s leading online retailer, challenged that by using 10,000 servers, each with 96 powerful processors, to simulate the workings of Google’s new chip, drawing on the US company’s published plans. The results are a reminder that existing computer architectures are far from played out—and suggest that Google’s planned demonstration with its quantum chip wouldn’t be beyond the reach of conventional computers. “There was a lot of hope that this future processor will achieve quantum supremacy,” says Yaoyun Shi, director of Alibaba’s Quantum Lab. “Our result shows that this enthusiasm is perhaps too optimistic.” He says the company achieved its result by devising better ways to divide the task of simulating quantum computing operations across many computers working together.

Alibaba’s results moved Graeme Smith, a professor at the University of Colorado to tweet a link with the comment “wow.” Google’s Bristlecone appears to be the most capable quantum chip yet, Smith tells WIRED, but Alibaba’s results suggest error rates are still too high. “This suggests that we won’t be seeing a demonstration of quantum supremacy anytime soon,” he says.

Google’s Boixo counters that Alibaba’s simulations weren’t detailed enough to be definitive. Work on better simulations—like Alibaba’s study—is one reason Google has been working on new ways to test quantum supremacy, which Boixo says shouldn’t require big hardware upgrades. Hen of USC says this will, in turn, spur researchers trying to squeeze more from conventional computers. “I’m sure the goalposts will keep moving,” he says.

Alibaba’s rise in quantum computing has been rapid and demonstrates China’s technology ambitions. Google has been working on quantum computing since 2006, initially using hardware from Canada’s D-Wave. The Chinese retailer entered the field in 2015, teaming up with the state-backed Chinese Academy of Sciences to open a new research lab. In February the company made an experimental 11-qubit chip available over the internet. China’s government has committed $10 billion to build a new national quantum lab.

Those projects are part of a growing international contest: The European Union is planning a $1.1 billion investment in quantum research. The Trump administration has highlighted quantum computing in budget guidance. Although the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy has shrunk significantly under President Trump, in December the group got its first dedicated quantum computing expert—Jake Taylor, a researcher from the University of Maryland.

Google set up its own quantum hardware lab in 2014, bringing in Martinis from UC Santa Barbara to lead the group. The company’s recent talk of achieving quantum supremacy has irked some others in the field, who say building up the milestone as a definitive moment risks overhyping how close practical quantum computers really are. Intel CTO Mike Mayberry told WIRED this week that he sees broad commercialization of the technology as a 10-year project. IBM has said it can be “mainstream” in five.

Alibaba’s Shi doesn’t deny that quantum supremacy—when it comes—will be important. But he suggests that researchers at Google and elsewhere should be more philosophical about it. “For device physicists to worry about when to reach supremacy is like worrying about when your baby is going to be smarter than your dog,” he says. “Just focus on taking good care of her and it’ll happen, even though you aren’t sure when.”

Tech

via Wired Top Stories https://ift.tt/2uc60ci

May 19, 2018 at 06:06AM

Vermont Legislators Pass Law Allowing Drug Imports

https://ift.tt/2KDMXjz

This week, Vermont passed a first-in-the-nation law that would facilitate the state’s importation of prescription drugs wholesale from Canada. It represents the state’s effort to tackle head-on the issue of constantly climbing drug prices.

Other states, including Louisiana and Utah, have debated similar legislation and are watching Vermont’s progress closely.

After all, the issue of drug importation polls well across the political spectrum and has been endorsed by politicians ranging from candidate Donald Trump, before he became president, to liberal firebrand Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

So how much impact might a state law like this actually have?

Trump has since stepped back from his campaign position, and the White House did not include drug importation in its proposal last week to bring down drug prices.

And cautions abound that importation may not actually save that much money as questions swirl about whether the policy undermines drug safety standards.

Kaiser Health News breaks down the challenges that lie ahead for importation champions, and what it shows about the future of the drug pricing fight.

Just having a law like Vermont’s on the books is not enough to legalize importation. The next step is for the state to craft a proposal outlining how its initiative would save money without jeopardizing public health. The proposal, in turn, is then subject to approval by the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

HHS has had yea-or-nay power over state importation programs since at least 2003, because of a provision included in the law creating Medicare Part D. But it’s never actually approved such a plan. And—despite mounting political pressure—there’s little reason to think it will do so now.

In the past weeks, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has come out strongly against importation, calling it a “gimmick” that wouldn’t meaningfully bring down prices.

He also has argued that the U.S. government cannot adequately certify the safety of imported drugs.

HHS declined to comment beyond Azar’s public remarks.

Importation backers—including the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), which helped craft Vermont’s bill and has worked with state lawmakers—hope he’ll reverse these positions. But few are optimistic that this will happen.

“I don’t expect that Vermont alone will be able to bring sufficient pressure to bear on Secretary Azar to convince him to change his mind,” said Rachel Sachs, an associate law professor at Washington University in St. Louis, who tracks drug-pricing laws.

Perhaps not much. Canadian wholesalers might stand to lose financially.

After all, pharmaceutical companies that market drugs in the United States might limit how much they sell to companies that have supply chains across the border. They could also raise their Canadian list prices.

“Almost inevitably, Canadians would cease getting better prices,” said Michael Law, a pharmaceutical policy expert and associate professor at the University of British Columbia’s Center for Health Services and Policy Research. “If I were a [Canadian] company, I wouldn’t want that to occur—and [drugmakers] could take steps to limit the supply coming north. … It probably results in [Canadians] getting higher prices.”

Trish Riley, NASHP’s executive director, dismissed this concern, saying some Canadian wholesalers have indicated interest in contracting with Vermont.

Vermont would still have to prove to HHS that its proposal would yield “substantial” savings. This won’t be easy.

In fact, some analysts suggest savings would be limited to a narrow slice of the market.

Importation could bring down the price of some generics and off-patent drugs by increasing competition, suggested Ameet Sarpatwari, a lawyer and epidemiologist at Harvard Medical School who studies drug pricing.

Many generic drugs have also seen substantial price hikes in recent years—but curbing these costs is only part of the equation.

“It’s not a panacea for the drug-pricing reform or high drug prices as a whole,” Sarpatwari said.

Branded drugs, which drive much of the American problem with prescription price tags, are distributed by a single company and, therefore, that company has greater control over supply and pricing pressure.

The worry, according to critics, is that American regulators can’t effectively determine whether imported drugs meet the same safety standards as those sold directly in the United States. A year ago, a bipartisan group of former Food and Drug Administration commissioners made that very argument in a letter to Congress.

Azar has argued this same point, as has the influential pharmaceutical industry, represented by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America.

“Lawmakers cannot guarantee the authenticity and safety of prescription medicines when they bypass the FDA approval process,” said Caitlin Carroll, a PhRMA spokeswoman, in a statement released on Vermont’s law.

This position, though, draws skepticism.

In cases of drug shortages or public health emergencies, the United States has imported drugs. And many Canadian and American drugs are made and approved under similar standards, Law noted.

“In terms of general safety, it is kind of nonsense. … We share plants,” he said. “The idea that Canadian drugs are somehow unsafe is a red herring.”

An argument in favor of plans like Vermont’s focuses on the idea that because the state would import drugs wholesale—rather than enabling individuals to shop internationally—it would be able to address concerns about safety or quality, Riley said.

Plus, Sarpatwari suggested, the government has resources to track drugs that come from Canada, especially if a drug were recalled or ultimately found to have problems.

“Our technology is catching up with our ability to do effective monitoring,” he said. “Particularly when it’s coming from a well-regulated country, I think there is less fear over safety.”

The federal government has taken little action to curb rising drug prices—though HHS now says it plans to change that.

So far, state legislatures have been pushing for laws to penalize price gouging, promote price transparency or limit what the state will pay.

But state initiatives often require federal permission.

Vermont’s law, which is arguably meaningless without HHS’ say-so, is just one example.

Sarpatwari pointed to a request from Massachusetts to develop a drug formulary for its Medicaid insurance program—theoretically giving the state more leverage to negotiate cheaper prices by reducing how many drugs it’s required to cover.

That proposal also is contingent upon approval from HHS. The administration has been publicly silent, though some news reports suggest it leans toward rejecting the request.

Meanwhile, Sachs said Vermont’s law, and others like it, will challenge the White House to show its mettle in taking on drug costs.

“We’re seeing explicit actions by the states to put pressure back on the federal government,” Sachs said. “The administration is publicly committed to lowering drug prices. It is being asked to make decisions which will, in some ways, show how much it really is attempting to accomplish that goal.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.

This story was originally published by Kaiser Health News on May 18, 2018. Read the original story here.

Tech

via Scientific American https://ift.tt/n8vNiX

May 19, 2018 at 11:00AM

A new Wi-Fi system could help your home network, if companies sign on

https://ift.tt/2Lbld76

The devices in your home come from different manufacturers, and that’s usually fine. You might have a Samsung smart television, a TP-Link router, and an iPhone, but they can probably all connect to your Wi-Fi network. That’s one of the nice things about Wi-Fi: The protocol is indifferent to who made the device. For that, you can partly thank the Wi-Fi Alliance, an industry organization that certifies devices to show that they play nicely with the other gadgets on the invisible Wi-Fi playground in your home.

But the way Wi-Fi is distributed throughout our abodes is changing. Sure, one router can broadcast the signal from a single location. Another option, however, is a mesh network, in which multiple points throughout your home work together to send out the signal from various spots, forming a mesh, or web. It’s a good strategy for people with big homes, and popular mesh-network makers include Eero and Google Wifi. Now, the Wi-Fi Alliance has unveiled a novel initiative designed to make sure that mesh networks in your home, even with nodes made by different companies, work together.

The Wi-Fi Alliance calls the new project EasyMesh. Kevin Robinson, vice president for marketing at the organization, says that the context for the initiative is that people are increasingly adding smart home devices throughout their homes, and those devices, especially gadgets like TVs that stream high-def content, require robust internet connections. In short, a router in one room might not cut it for some people, but a mesh network, with a strong signal in lots of places, could. One of the benefits of EasyMesh, Robinson says, is that someone could “very easily add Wi-Fi EasyMesh access points, regardless of vendor.”

Translation: The parts of your mesh network providing a signal to all your devices could come from different companies. Right now, individual companies make different mesh networks that are designed to work with their own equipment. (Although you can always add range extenders from different companies to your network.)

Of course, standards—which generally help consumers—require companies to agree to them if they’re going to work well. “I think it’s a great idea,” says Swarun Kumar, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. “The question is how quickly will the industry embrace and adopt this—it’s a little bit unclear.” After all, a company that doesn’t participate in the EasyMesh standard can keep its consumers buying its own products.

“It should lead to more openness and more choice for the consumer,” Kumar adds, if the standard is easy enough for the companies to adopt.

Some companies, like router-maker TP-Link, are supportive of the new protocol. “TP-Link is working closely with the alliance on the final development of the standard and plans to be one of the first companies to support EasyMesh when it becomes available,” Derrick Wang, the director of product management for TP-Link USA Corporation, says via a spokesperson.

Others aren’t currently hopping on board. Eero spokesperson Zoz Cuccias said via email: “We will continue to follow the draft development of the WiFi Alliance’s EasyMesh. For now, we’re fully devoted to TrueMesh, the most reliable and secure mesh available to consumers today.”

Ditto with Google, which makes Google Wifi. “We’re excited to see the industry acknowledging the consumer benefits of mesh technology and we’ll be monitoring the progress of this proposed standard as it evolves,” a company spokesperson said via email. “Google Wifi is built on 802.11s, the IEEE standard for Wi-Fi mesh, and we’ll continue to focus on providing the best experience to consumers.”

It’s early days for the new certification. Robinson, of the Wi-Fi Alliance, says that they respect the decisions that companies make, and that they want to keep pushing innovation in the field forward. “Ultimately, any of the certifications that Wi-Fi Alliance develops are optional,” he says.

Tech

via Popular Science – New Technology, Science News, The Future Now https://ift.tt/2k2uJQn

May 17, 2018 at 04:24PM

The FDA approved a drug that treats opioid addiction that isn’t addictive itself

https://ift.tt/2ka1B74

This week, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave final approval for a drug shown to mitigate the symptoms associated with opioid withdrawal. It’s not the first treatment designed to help those with opioid addiction, but it has a distinguishing feature: It’s the first one that isn’t an opioid itself, and has no addictive component.

Medications exist now to assist those trying to break their addiction to pain medications, but all of those are opioids themselves, given in gradually lower doses to mitigate the symptoms associated with addiction and withdrawal. But the problem with this is that some patients remain addicted to and dependant on opioids in the long term, even if the drugs they’re receiving come under a doctor’s guidance and at a much lower dose. The idea behind the newly approved medication Lucemyra is to treat those same symptoms without including an addictive component.

The active ingredients in the pill bind to cell receptors in the body that lower the production of norepinephrine. This hormone works as part of your body’s fight-or-flight response, working in concert with adrenaline to increase your blood pressure, heart rate, and alertness when necessary.

While researchers don’t completely understand the mechanisms involved, they believe the fight-or-flight response, also known as the autonomic nervous system, plays a key role in the development of the classical symptoms of opioid withdrawal—which include nausea, anxiety and agitation, increased heart rate, severe aches and pains, and sleeping problems. The two clinical trials (which included a total of 866 adults) that enabled Lucemyra’s approval showed the drug worked to lessen the severity of those symptoms.

The impetus behind this medication approval, FDA officials say, is to provide more options for people with opioid use disorders. However, according to the FDA, the drug’s main purpose for now is to help those with more severe addictions. For those taking opioids as part of a pain management regimen, the method to wean off of the addictive meds remains the same: A physician-managed, slow taper of the medication, meant to lessen the withdrawal side effects and help the body adjust to being off the drugs.

But for people with what’s called opioid use disorder—which often starts with an opioid pain medication prescription—physicians often swap in another opioid medication, such as methadone, buprenorphine, or naltrexone. Doctors then gradually taper them off those drugs with the hope that the body will continue to adjust. These opioid alternatives tend to be less potent than either opioids typically prescribed for pain or ones commonly used recreationally, like heroin. For example, Buprenorphine is what’s known as an opioid partial agonist; its addictive side effects are similar to other opioids, but it’s far less dangerous overall. And at low tapering doses, it’s far less likely to initiate withdrawal symptoms than a gradual taper of a full opioid agonist.

This new drug offers doctors a way to help severely addicted patients without switching them to another opioid, but it remains to be seen how it will fit into the existing medical toolbox. However, its innovation is important: In 2017, the U.S. Department of Health declared the opioid addiction crisis in America to be a public health emergency. In 2016, 2.1 million people had an opioid use disorder, resulting in over 42,000 deaths. Looking for safe and effective ways to treat this condition that minimize the drugs’ addictive nature could significantly lessen both those numbers.

Tech

via Popular Science – New Technology, Science News, The Future Now https://ift.tt/2k2uJQn

May 18, 2018 at 02:51PM

Patent Depending, The “Nonsense” Inventions of Steven M. Johnson at Maker Faire

https://ift.tt/2KCw4G2

I have followed the career and work of “nonsense” inventor, Steven M. Johnson, for decades. I wrote about his work, back in the day, at both The Futurist magazine and early Wired. Steven has shown his invention illustrations at Maker Faire Bay Area in the past and he’s back this year with more brilliant and bizarre design ideas.

Anyone who has seen Steven’s work knows that it is funny, epically whimsical and silly, but it is ultimately far from useless. These wacky, cockeyed design ideas say a lot about the nature of the human character, our love/hate relationship with technology, and our modern notions of work, leisure, and our seemingly endless desire to use technology to give us more slack, regardless of how inappropriate that technology may end up being. Steven’s designs are so well conceived, and often so close to technologies that could actually exist that they do funny things to your head; they often end up inspiring real, more sober design ideas. And ultimately, it is this triggering of useful lateral thinking that makes these inventions so compelling.

Here is a TED Talk that Steven gave on his work:

As the comedian Steven Wright likes to say: “I’m a peripheral visionary. I can see into the future, but just off to the side.” I can think of no more clever and inspiring peripheral visionary than Steven M. Johnson.

If you are at Maker Faire Bay Area this weekend, come see Steven in Zone 2 of Expo: West.

Tech

via MAKE https://makezine.com

May 18, 2018 at 03:35PM

The True Story of How Laurel Became Yanny

https://ift.tt/2IrsQs4

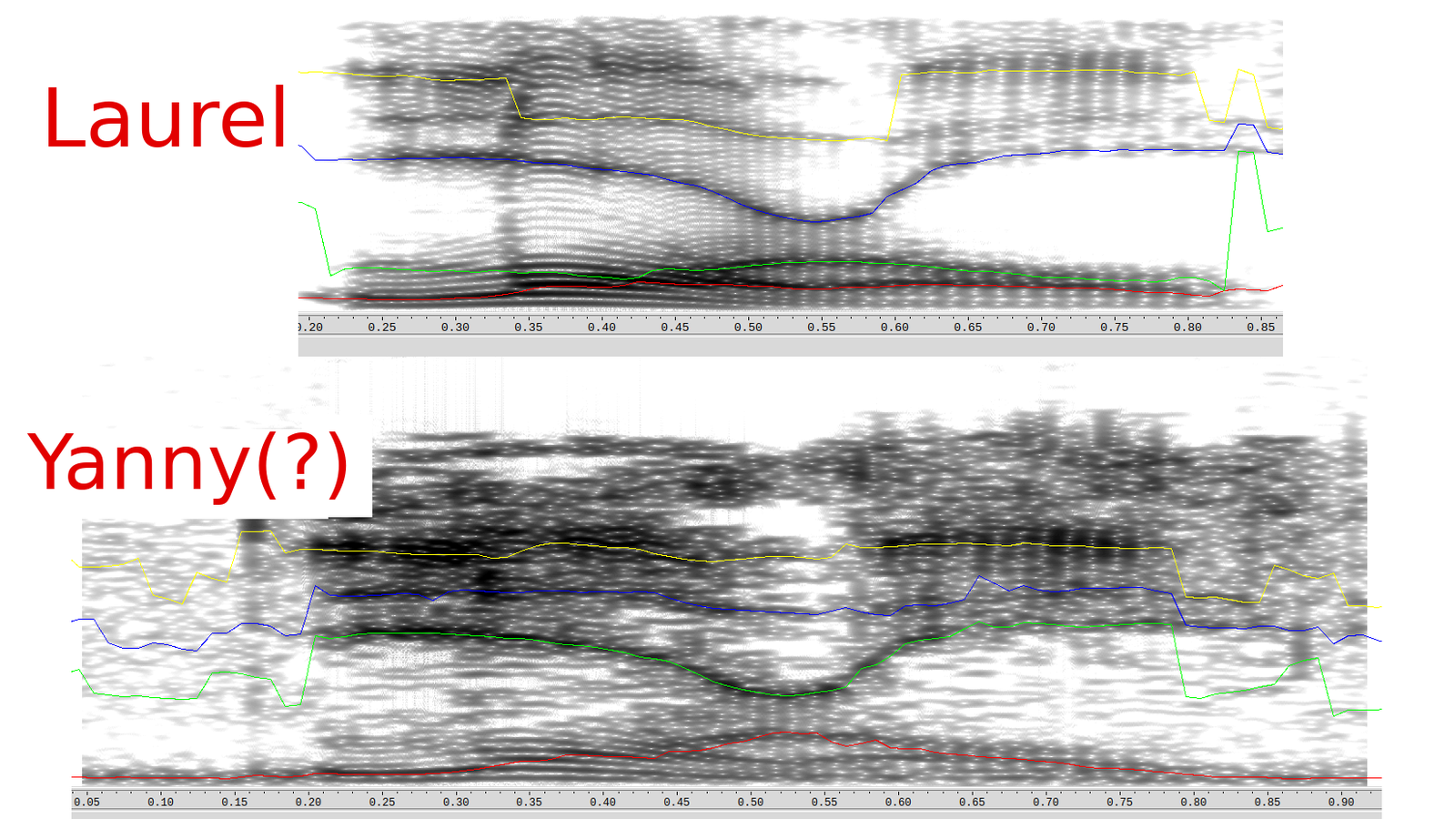

In the beginning, the laurel-or-yanny clip said laurel and nothing but laurel. Here is the original version of the clip, recorded by an opera singer working for Vocabulary.com. Chances are, you’ll hear it as laurel too. Let’s compare it to the viral clip and we’ll see exactly what changed, and why half of us hear the viral clip as yanny.

The original recording came from Vocabulary.com’s 2007 effort to include pronunciations for the site’s most commonly looked-up words. This was the recording made for the word laurel. It was spoken by Jay Aubrey Jones, one of eight singers commissioned by the company to read the words from home using a provided laptop, microphone, and portable sound booth. (Opera singers are trained to read IPA, the pronunciation code that dictionaries also use.) Jones personally read about 36,000 words for the site.

There were so many sound clips to process, says Vocabulary.com co-founder and chief technical officer Marc Tinkler, that software did everything automatically: trimming the beginning and end of each file, applying a noise-reduction filter if needed, and converting to the mp3 format that saves space and bandwidth.

The beauty of the mp3 format is that it can compress sound files into a small enough amount of space to easily share around the internet. The drawback of the mp3 format is that it does this by removing sounds from the recording and introducing some glitchy, tinny noises. If you’re okay with a file that’s only slightly compressed, you can leave in most of the original sound information. But, says Tinkler, “this was back in 2007 or 2008, so we were pretty aggressive in the downsampling process.”

I asked Tinkler if there was any chance he had the original file for comparison. He found it on a DVD in a storage closet, and uploaded it to Soundcloud for all to hear. Technically this is not the exact original, because Soundcloud provides it as an mp3 but it was originally recorded in an even higher quality format. But it’s more original, shall we say, than the version you and your friends have been arguing over. And it’s clear enough that we can now tell exactly what happened when the file was compressed.

Compressing the laurel clip had a major casualty: the second speech formant. Without this part of the sound spectrum, an L can sound like “ee” and an R can sound maybe a little bit like an N.

Here’s why. Sound waves each have a frequency. The higher the frequency, the higher the pitch we hear. But the sound of speech includes many frequencies at the same time. Our ears and brains pick out the strongest frequencies from this mess of sound. Speech scientists call these formants. The two lowest-pitch formants give us enough information to tell the difference between one vowel sound and another.

If you open up a sound file in an analysis program, you can see these formants. That’s exactly what my father, a speech scientist at California University of Pennsylvania, did when I showed him the viral clip. He opened the mp3 in a program called Wavesurfer and proceeded to show me, on his laptop at the kitchen table, how I was wrong to hear laurel because the formants match up to the sounds “ee”, “a”, something ambiguous that could be an “n”, and a final “ee.” Yanny.

But, he conceded, there’s just enough ambiguity that you could hear laurel if you really wanted to. (He suspected at first that the file was carefully crafted to be ambiguous, an intentional audio illusion.) For the record, I have never heard anything but laurel from this file.

My dad can read the formants just from the black-and-white spectrogram view, but Wavesurfer helpfully detects them and color-codes them. Wavesurfer agrees with my dad, and reads this file as saying yanny. But if you give it the original file, it highlights a different set of formants: the ones that say, very clearly, laurel.

To understand what happened, take a look at the red and green lines. These are the first two formants, which we’ll call F1 (red) and F2 (green). They both hover around the bottom of the spectrogram. A third formant, F3, floats high above them in blue, dipping down very close to the F2 during the R sound in laurel.

But then look at the processed clip, the one that you’ve been sharing with your friends. (Click the arrow in the slideshow above.) It’s noisier overall, thanks to the mp3 compression. That noise blurs out the difference between the F1 and F2, leaving both Wavesurfer and our brains to figure there’s maybe only one formant down there, the F1. That means that the higher-up line, the one that dips down in the middle, looks like it must be the F2.

At the beginning of the clip, the F1 and F2 down low next to each other are compatible with hearing an L. But if F1 is down there, and F2 is way up above 2000 hertz, that’s an “ee” or a Y sound. Obliterating the second formant changes how we interpret the sound.

The viral, processed clip doesn’t entirely remove the second formant, just makes it harder to discern among the noise. If you’re expecting to hear laurel, and if your ears and brain can find two formants in the low frequencies, you can still hear it as laurel. But to a different person, the sounds of yanny might stand out more, as Gizmodo reported earlier this week.

So what about those videos and slider tools that show you can change what you hear by listening to just the high or the low frequencies? It turns out that phenomenon, too, comes down to the speech formants.

If you cut off the higher frequencies, you’ll be left with just the lower part of the spectrum, where the original F1 and F2 were. Your brain will work a little harder to be able to tell those two formants apart, instead of locking on to what it thinks is an F2 higher up. By contrast, if you listen to just the higher frequencies of the clip, your brain picks up on the real F3 as a possible F2, and assumes there must be a single F1 down in the lower part of the spectrum.

So this trick changes your perception not because yanny is “in” one part of the spectrum and laurel “in” another, but because either way your brain is only hearing some of the formants, and is guessing at what the others might be.

Tech

via Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com

May 18, 2018 at 10:38AM